March 25, 2010

(Note: if you have read this introduction to the G Series, please go to the blog post immediately after this introduction to read the latest article in this series.)

A caveman makes his thoughts visible by drawing pictures on cave walls. My five-year old grandson Elias draws a picture (“LOLO” means grandfather) to convey his idea of me (he thinks my tummy is too big). The invention of writing standardized how a person converts her tacit ideas into explicit forms that can be read by another. It ushered a leap in mankind’s evolution as an intelligent being.

Knowledge management involves thinking and deciding together, as a preparation to acting productively together. KM is about producing explicit group knowledge from tacit individual knowledges. One reason KM is an exciting field for me is that I see many new tools emerging and evolving for making visible how we think together.

Let us start to call these tools “grawing-and-griting” (or G&G) for group-drawing and group-writing. Such tools are essential in how mankind learns how to talk productively together, how to reach consensus or resolve conflicts, and how to enable themselves to solve especially those problems that need concerted action. These tools I believe can contribute to ushering another leap, a leap this time in mankind’s evolution as an intelligent social being.

–

–

The diagram above illustrates the difference between the individual process of drawing and writing, and the group process of “grawing-and-griting”. Drawing and writing by an individual is the externalization of his thinking alone; G&G is the externalization of a group’s process and product of thinking together. The diagram again uses the framework of Ken Wilber and the same color coding I used in my previous blog posts:

What Grawing-and-Griting is Not

Effective group action is not always the result of effective group thinking and planning. For example, an orchestral piece beautifully performed by a group of musicians is effective group action, but the musical scores used by the different musicians in the orchestra are most likely written by only one individual, the composer. The set of musical scores that constitute a symphony is not an example of group-writing or griting.

Similarly, when a basketball coach draws on a board the moves and tactics he wants his players to execute, he is making an individual drawing, not a group-drawing or grawing.

A group of jazz musicians playing together is effective, simultaneous group improvisation. They do constant sensing of each other as they play. However, this effective group action is a purely tacit process. It is not G&G because G&G involves making visible or explicit the thinking processes in a group.

Blogging and writing a diary entry are not G&G because they are solitary externalizations. Effective thinking together entails disclosing one’s thoughts to the group (e.g. Senge’s Left-Hand Column) or one’s reasoning processes for the group to examine (e.g. Senge’s Ladder of Inference). Grawing-and-griting is groupwide externalization: it is converting individual tacit thoughts to explicit or visible images and/or texts that everyone in the group can see and can think interactively with.

Below are the previous (with links) and forthcoming (no links) blog posts under the G Series. To read about a previous blog, click on its link.

G1. Group mind mapping

G2. Live griting the minutes of a meeting

G3. “Track changes” and wiki are sequential griting

G4. Tabletop grawing in a Knowledge Cafe

G5. Using small group carousels for collective idea generation (guest blog by Bruce Britton)

G6. Community-based resource mapping

G7. Using Post-its to arrange ideas

G8. Telling you my thoughts: Senge’s Left-Hand Column

G9. Telling you my reasoning process: Senge’s Ladder of Inference

G10. Group planning with Google Docs spreadsheet

G11. Collaborative cause-and-effect analysis

G12. Telling you my assumptions and interests

G13. Stakeholders’ co-construct a Problem Tree

G14. Grawing a fishbone diagram

G15. Asynchronous-sequential versus live-interactive

G16. Crafting diagnostic ideagrams

G17. What shall we name this?

G18. Choosing and using metaphors

G19. Grawing a shared vision and a shared logo.

Come back soon and check what is new!

—

Thanks to Wikimedia Commons for the use of the image in this blog post.

=>Back to main page of Apin Talisayon’s Weblog

=>Jump to Clickable Master Index

Tags: collective vision, community-based resource mapping, diagnostic ideagrams, fishbone diagram, flag, Google docs, grawing, griting, group drawing, group writing, herald, KM, KM tool, knowledge management, logo, mental model, mind map, problem tree, stakeholders' problem tree, track changes, wiki, writing

Posted in innovation, KM tool, knowledge management | Leave a Comment »

July 17, 2010

[This is a guest blog article by Bruce Britton. Please see his introduction in the previous blog post.]

During a recent training course on ’Reflective Practice’ that I facilitated for the Asian Development Bank and invited guests I used a technique that enables groups to work together, record their ideas and build on each others’ contributions. I know the technique as ‘Small Group Carousel’ and it involves dividing a task into stages, allocating each stage to a small group, asking each group to list out their ideas then move on to each of the other lists, discussing the ideas that are already there and adding their own ideas. The groups move round each list until they arrive back at their original list but this time with the other groups’ contributions added.

This is how we used the Small Group Carousel technique on the course. First of all I introduced ‘Bob’ who needed our help (see figure below). I explained that Bob’s challenge was to develop a good practice guide on Reflective Practice. The task seemed to me to divide into three stages – before, during and after – so participants divided into three groups with each group taking responsibility for generating ideas on one of the three stages. Each group was given a different coloured marker pen to note their ideas on a flipchart sheet.

After about ten minutes the groups were asked to move on to the next stage, so those working on the ‘before’ stage moved on to the ‘during’ stage; those who had worked on the ‘during’ stage moved to the ‘after’ stage, and so on. The groups then read through the ideas they found on the flipchart sheet and added their own ideas, or annotated the existing ideas. They were not allowed to delete ideas but could question or comment on those that were already written on the flipchart. After about five minutes they were asked to move on again and add to the ideas on the third flipchart (which by this time already had the ideas of two groups written on it). Finally, the groups were asked to move to the sheet that they had started and to read and discuss the collective thoughts and ideas of all three groups.

Here are the ideas generated for each stage:

Note that each group used different colored pens (black, blue and green) enabling everyone to see how each group built on the ideas of each other.

You can see that each group has not only generated new ideas but annotated those written by other groups. This provided a rich amount of information to discuss. The next stage was to negotiate overlaps, delete ideas that everyone agreed were not suitable, and reach consensus about what should be involved at each stage. Using different coloured pens made it easier to remember which group had written which comments.

The outcome of the carousel process is a collaboratively produced and owned set of ideas that draws on the collective experience of those participating. The dynamics of the process makes it easier for individuals to contribute (because work groups are smaller) and generates ideas that both build on and challenge earlier ideas. The technique can be adapted in many ways and used in a range of settings from team meetings to peer assists.

—

Note that there is an embedded link in this blog post. It shows up as colored text. Click on the link to open (in a new tab) the webpage pointed to.

=>Back to main page of Apin Talisayon’s Weblog

=>Jump to Clickable Master Index

Tags: Bruce Britton, KM tool, knowledge management, organizational learning, reflective practice, small group carousel, thinking together

Posted in dialogue, KM for development, KM tool, knowledge management | Leave a Comment »

July 15, 2010

To my blog followers,

I have not been able to post blogs for more than two months because I had been sooo so busy travelling around. I was in several rural areas in the Philippines in the provinces of Southern Leyte, Capiz and Oriental Mindoro. I made a trip to Tokyo together with other KM experts to prepare KM guidelines for SME owners and managers. I was in Bangladesh earlier this week and I am now in Pakistan evaluating productivity projects. In the next weeks I will travel to Vietnam, Malaysia and Thailand.

Cheers! I intend to resume the G series promptly. I will also post two guest blogs. Bruce Britton, an expert from U.K. in learning organizations applied to the development sector, and Norman Lu, a KM specialist from the Asian Development Bank, promised to contribute blog articles on the topic of our G series: making visible how we think together.

The next blog will be about “Using Small Group Carousels for Collective Idea Generation” by Bruce.

Bruce is a principal of Framework (a UK-based consultancy organization established in 1985 and working exclusively with non-profit organizations). Before joining Framework he worked for Save the Children UK as a project manager, Staff Training and Development Officer and Regional Adviser (South Asia) on Human Resource Development. He has twenty five years of experience of working as a consultant and facilitator and has spent fifteen of those working with culturally and professionally diverse groups of development practitioners and managers in over thirty countries across Africa, Asia and Europe.

Bruce has designed and facilitated many courses and workshops on organizational learning and knowledge management for clients in the development sector including the Asian Development Bank, RDRS Bangladesh, CHF Canada, Oxfam NOVIB, TearFund, Swedish Mission Council, PSO, Netherlands, PLAN International, CARITAS Sweden and BOND. He has conducted organizational learning reviews and strategy development workshops for many international NGOs including SNV (a Netherlands based capacity building NGO working in over thirty countries), the Aga Khan Foundation and INTRAC (the International NGO Training and Research Centre, Oxford).

Bruce also has a blogsite on “Motive, Means and Opportunity.” It is about learning and development in NGOs.

I will post his guest blog within the next two days.

—

Note that there are embedded links in this blog post. They show up as colored texts. Click on a link to open (in a new tab) the webpage pointed to.

=>Back to main page of Apin Talisayon’s Weblog

=>Jump to Clickable Master Index

Tags: Bruce Britton, knowledge management, Norman Lu, organizational learning

Posted in KM for development, knowledge management, learning | Leave a Comment »

April 19, 2010

Knowledge Cafe is a popular tool for creative exploration and brainstorming together – thinking processes which are more productive if participants’ right brains are more engaged. However, about 94% of people are left-brain dominant and it takes effort and different process techniques to engage their right brains.

A process technique to engage people’s right brains more is by making them draw instead of letting them do talking or writing. Talking and writing words are left-brain activities, while drawing and using images and symbols are right-brain activities.

In a Knowledge Cafe, drawing is encouraged by placing large sheets of Manila or kraft paper as well as several colored pens or crayolas on the table. Participants are free to draw as they talk and think together. If many participate in the creative thinking and drawing process, the evolution of the drawing on the tabletop makes visible to the group what they are thinking together. They are “grawing” (=group drawing)!

Grawing is more a right-brain activity while griting is more a left-brain activity. Tabletop grawing in a Knowledge Cafe is a right-brain activity, while live griting the minutes of a meeting is a left-brain activity. In the grawing-and-griting or G&G Table in the previous blog, the upper rows are more right-brain while the lower rows are more left-brain activities.

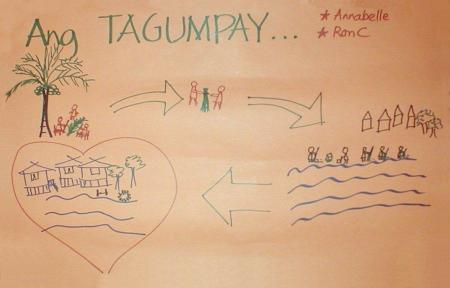

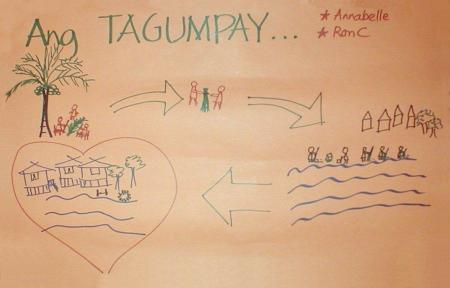

Below is the result of tabletop grawing where participants together drew their collective idea of what is “successful community development”. “Tagumpay” is the Tagalog word for “success”.

One of the participants, Annabelle, verbalized their grawing as follows (translated from Tagalog, shortened and edited while maintaining the essential ideas):

For us, the start of development is like making walis tingting.* [*Note: “Walis tingting” is a local broom (“walis”) consisting of about a hundred coconut midriffs (“tingting”) tied together. This coconut broom represents a well-known local metaphor for unity: one coconut midriff cannot do anything; it is powerless. But when many are tied together (unity of the community), they gain strength and efficacy.]

First, the leafy part from each coconut leaflet is removed by a knife to produce one tingting [midriff]. This is like individual discipline: it is difficult or painful but when done, it is a small success. Then many tingtings are tied together into a broom. This is community discipline and unity – a bigger success. With a broom you can clean the seashore of garbage. If the community is united and a project answers community needs – when families get their own house, land and livelihood and they can help themselves and the community – then the project is successful. However, that is not the end-all of success.

The last stage [see last arrow pointing to houses inside a heart] is when you no longer need the broom because every community member understands and respects or feel responsible for the environment, and no longer throws garbage. That is far greater success.

—

Note that there are embedded links in this blog post. They show up as colored texts. Click on a link to open (in a new tab) the webpage pointed to.

=>Back to main page of Apin Talisayon’s Weblog

=>Jump to Clickable Master Index

Tags: G&G, grawing, grawing-and-griting, griting, group drawing, group writing, KM, KM tool, Knowledge Cafe, knowledge management, left brain, right brain

Posted in KM for development, KM tool | Leave a Comment »

April 14, 2010

ICT-mediated tools are emerging which facilitate collaborative editing and authoring among a group. By our definition of “griting” these tools are griting tools. They do help a group think together.

These tools can be grouped into two: sequential griting tools and real-time synchronous collaborative griting tools. MS Word “Track Changes” and wiki are sequential or asynchronous griting tools. Editors take turns; one editor starting only after the previous editor had finished. There are many ICT-mediated tools for real-time synchronous editing; those that are web-based can enable people in different geographic locations to collaboratively edit a paper together. Some examples are: LivePad, Google docs spreadsheet, MoonEdit and EtherPad.

These griting tools use mainly text, while mind mapping and other “grawing” tools use drawings, diagrams and other images (see previous blog post on “G1 – Group Mind Mapping”). In both cases, the grawing-and-griting tool facilitates a crucial KM process: a group thinking together.

The diagram below gives you a quick birds-eye view of grawing-and-griting tools I will cover in Blog Series G. Do you have any comments, additions or suggestions?

—

Note that there is an embedded link in this blog post. It shows up as colored text. Click on the link to open (in a new tab) the webpage pointed to.

=>Back to main page of Apin Talisayon’s Weblog

=>Jump to Clickable Master Index

Tags: asynchronous, EtherPad, G&G, Google docs, grawing, grawing-and-griting, griting, group drawing, group writing, KM, KM tool, knowledge management, live griting, LivePad, MoonEdit, on-line griting, real-time collaborative editing, RTCE, synchronous, track changes, wiki

Posted in KM tool, knowledge management | Leave a Comment »

April 4, 2010

The minutes (=written record, transcript or documentation) of a meeting is an example of “griting” — it is a record of a group’s discussions and decisions. In this blog series, griting is what we call a visible representation of what a group is thinking or had thought.

The group mind map described in the previous blog is mainly “grawing” (=group drawing) while the minutes of a meeting is largely “griting” (=group writing).

The common and traditional way of writing the minutes consists of:

- A secretary takes notes and/or audio recording during the meeting.

- After the meeting he drafts the minutes based on his notes and/or by listening to the audio recording.

- Before the next meeting, the minutes may or may not be reviewed and corrected by one or more meeting attendees.

- In the next meeting, the group reviews, agrees on final corrections and approves the minutes.

This common method is prone to many errors:

- Days or even months pass between meetings. If no audio recording was made, the minutes is based on error-prone recall.

- Reconstructing what was said and decided from an audio recording takes 2-3 times longer than the duration of the meeting.

- If no audio recording was made, meeting attendees may have different recall of what was said and will have to spend extra time to decide what should appear in the minutes.

- The speaker can change his mind since the previous meeting.

- In the end, the minutes is a poor record of what had actually been said.

In live griting of the minutes of a meeting, the above errors are reduced.

In courts, special stenographic skills and machinery are employed to produce real-time transcripts of court proceedings as verbatim as possible. The main aim of a certified verbatim reporter is 100% accuracy of reporting. However, in griting the main aim is to make visible to a group what they are thinking. Griting is a tool for thinking together.

Live griting the minutes of a meeting can be implemented as follows:

- A secretary, using a laptop attached to an LCD projector, records the minutes of a meeting while the meeting is going on.

- The meeting attendees see on the projector screen the minutes as it is being written a few seconds after a statement is made or a decision is reached.

- Any meeting attendee can immediately correct the record, if needed, and the secretary immediately implements the correction.

- As the group goes through its thinking processes, the minutes gets written; constant interaction of the group with the secretary assures that the minutes evolves in a manner that reflects the result of the discussion with accuracy acceptable to the group — this is the essence of “grawing-and-griting” or G&G.

By the time the meeting is done, the minutes of the meeting is also done!

Furthermore, technology has now advanced to the point where the tool for G&G can be placed and collaboratively worked on-line. For example, an on-line meeting can be conducted among attendees from different geographical locations where everyone is talking and thinking together via a conference VoIP call and synchronously co-writing/editing an online minutes of the meeting as the on-line meeting is going on!

An inexpensive combination is conference VoIP call via Skype, and on-line co-writing/editing of the minutes using Google docs — a G&G technology within reach of most everyone to enable a geographically-dispersed group of people to think together!

—

Note that there is an embedded link in this blog post. It show up as colored text. Click on the link to open (in a new tab) the webpage pointed to.

=>Back to main page of Apin Talisayon’s Weblog

=>Jump to Clickable Master Index

Tags: certified verbatim reporter, court reporter, court stenographer, G&G, Google docs, grawing, grawing-and-griting, griting, group drawing, group writing, KM, KM tool, knowledge management, live griting, minutes, minutes of meeting, on-line griting, on-line minutes, Skype, VoIP

Posted in KM for development, KM tool | Leave a Comment »

March 28, 2010

A group mind map is a picture of the consensus of a group about an idea or topic. The example below is the product of a group mind mapping exercise that I facilitated for a class of Malaysian educators in 2005 on the topic “How Do We Learn” (click on the map to see a bigger and better image in another tab). This sample mind map follows the basic structure of Tony Buzan’s mind maps: the topic is stated in the central oval and the sub-topics are portrayed as main branches and sub-branches. This mind map is an image that communicates the consensus of the group on what are the components and scope of the topic.

A group mind map is the product while group mind mapping is the process of producing it. The group process is interactive discussion to reach group decisions such as:

- Consolidating ideas from individual members of the group

- Clustering or re-clustering of ideas

- Naming or labeling a cluster

- Deciding what are the main branches and what are the sub-branches

- Adding or removing branches

- Collapsing several branches into one

- Disaggregating a branch into several branches

- Discussing differences in thinking and arriving at a consensus on the above.

What is essential in the group-drawing or “grawing” process is that the group mind map must constantly and immediately reflect every group decision. I implement this using a flexible mind mapping software (I use ConceptDraw Mindmap Professional) in my laptop which is connected to an LCD projector so that the group sees how the mind map is changed to reflect their decisions, such as:

- Creating or deleting branches or sub-branches

- Changing the label of a branch or sub-branch

- Detaching a branch/sub-branch and re-attaching it elsewhere

- Changing formats: mind map shapes, colors, text fonts, etc.

In this way, the mind map projected on the big screen in front of the group is an immediate reflection of the current thinking of the group. As the group revises its thinking about the topic, the group mind map in front of them changes accordingly. This is the essence of “grawing-and-griting”.

Last Friday, I formulated and showed the “First-Pass DRR-CCA Mind Map” below to a group of government executives from around 25 Asian countries, multilateral and bilateral donor agencies, international NGOs and various UN agency representatives (click on the map to see a bigger and better image in another tab). My purpose was to show them an example of how a single image can (a) convey the wide scope and different components of DRR-CCA or Disaster Risk Reduction and Climate Change Adaptation, (b) serve as a means for leveling off understanding of DRR-CCA among numerous stakeholders, (c) show a person any “blind spots” he may have on the broad field of DRR-CCA, and (d) provide an initial consensus that can be the basis of a knowledge taxonomy in DRR-CCA.

Because this mind map is the product of thinking alone by one person (me), this is NOT an example of a grawing-and-griting. Grawing-and-griting is the process and product of a group thinking together — the topic of this G Series of blogs.

Cheers!

—

Note that there are embedded links in this blog post. They show up as colored texts. Click on a link to open (in a new tab) the webpage pointed to.

=>Back to main page of Apin Talisayon’s Weblog

=>Jump to Clickable Master Index

Tags: Buzan, CCA, climate change adaptation, disaster risk reduction, DRR, grawing, grawing-and-griting, griting, group drawing, group mind map, group writing, KM, KM tool, knowledge management, mind map

Posted in KM tool, knowledge management | 3 Comments »

February 17, 2010

In 2006, I designed and facilitated a KM planning workshop for a new cross-functional KM Team. Among my objectives were (1) to motivate individual team members and (2) to show them in a concrete way the advantages of an expertise directory. I introduced a module that generated so much energy and enthusiasm among the team members that I repeated this module in other KM workshops for other organizations.

This is how the process flows:

- Individual seatwork: Each team member is provided a 3′ x 4′ kraft paper (or Manila paper) and a black felt pen. The instruction is: “List down all your talents, both technical and non-technical.” A few members asked guidelines on how to identify their talents. My answers were: “In what tasks/skills do your colleagues often ask you for assistance?” “Recall 1-2 very successful task/projects you did; what talents did you use?”

- Public posting: After a team member is done, she/he posts her/his work on the wall.

- Comment/feedback on each other: After all team members’ work had been posted around the walls, each team member is given a red (or any colored) felt pen, goes around and reads everybody else’s work. Anyone can write comments on anyone else’s work, e.g. “you forgot to add skill XX.” “I didn’t know you are good at YY!” “Prove it!” “You are too shy to mention skill ZZ!” “You should have joined Project @@!” Approval of a skill can be conveyed simply by a red asterisk.

- Answer comments: A team member, if she/he wishes, can write her/his reaction to a comment using a blue (or another color) felt pen.

- Plenary discussion: The team sits down and the facilitator leads a group discussion on insights and learning from the content (output) and process, and how they each felt about the process. As facilitator, I conclude by proposing “Let us collect your outputs and use this as inputs to your internal KM Team Expertise Directory.”

My own insights and learning from this module are:

- Team members often express surprise at knowing (and at previously not being aware of) many of each other’s talents. For example, they were very surprised that a medical doctor colleague had learned the skill of laying out bathroom tiles! KM is about harnessing talent, and it starts with recognizing it.

- The module was able to reveal to them the value of an expertise directory, especially one that includes both technical and non technical skills. For example, a non-technical skill (or a skill that does not appear in the ordinary CV or resume) that is useful for the organization is the ability to act as emcee (from “MC” or master of ceremonies) in a ceremony, conference or public event.

- The commenting process creates a space where KM Team members mutually acknowledge and affirm each other and their skills (this works well when the KM Team members know each other beforehand). It is a process that generates much interactive energy, team building and motivation.

- The process supports openness about one’s abilities and gaps, at the same time that it reveals individual styles and preferences such as hesitance to publicly announce one’s talents, and personal boundaries in self-disclosure. Such hesitance is acknowledged and respected by the group instead of challenged.

- All outputs taken together can reveal new systemic insights. In one organization, the CEO herself read the postings and then remarked “We have enough talent to put together a chorale and music band.”

What do YOU think? Tell us.

—

=>Back to main page of Apin Talisayon’s Weblog

=>Jump to Clickable Master Index

Tags: cross-functional KM Team, expertise directory, KM, KM Team, KM tool, knowledge management, motivating knowledge workers, motivation, non-technical skills, personal KM, personal knowledge management, self-disclosure, team energy, workshop exercise, workshop module

Posted in KM tool, knowledge management, personal knowledge management, training | 1 Comment »

February 7, 2010

The previous blog post is about knowledge of what works during contract negotiations. Knowing what does not work (or what are the risks) is also useful knowledge. After going through scores of KM contract negotiations, some successful and the others unsuccessful, let me share with you some of my experiences on what does not (or what may not) work and what are potential risks in contract negotiation.

- Find out who is the manager authorized to make scoping decisions? cost decisions? the final decision? At the start of the negotiation, ASK WHO are authorized to make the above decisions. (a) If no one in the organization is sure about the answers to the above questions (i.e. their contracting process is not yet standardized), you are in for a difficult and surprise-full negotiation process. (b) What is the INTERNAL POLITICS between them? You may be wasting your time while the managers perform their “power plays” during the negotiation process. If you are able to talk to the TOP EXECUTIVE or whoever will approve the contract, these risks can be better managed. KM projects not supported by the top executive are risky projects not worth going into. (c) If the manager who invited you to submit a proposal and the executive who will approve the contract are not the same person, find out if the latter is aware of the proposal invitation. If not, you can have a problem in your hands. Do not proceed any further until the latter not only knows about the invitation, but is also open and willing to consider your proposal.

- A client is after a desirable outcome, but you can only guarantee to deliver a set of outputs which contributes towards (but does not assure) that outcome. If the client wants his desired outcome to be your contractual deliverable, then propose instead that you GUARRANTY ONLY THE DELIVERABLES but not his desired outcomes.

- A client may keep asking details and more details about project methodology, or may want you to specify them in detail in your proposal. Beware: it is possible such a client may not be intending to award you the project or to hire you; he may be intending only to use your proposal to STEAL your methodology and do the project himself without you.

- If the client is not very definite about what he wants, or if there are differences in understanding of deliverables among the managers in the client organization, or between you and the client, then the deliverables must be specified clearly, CONCRETELY and in fine DETAIL. Avoid general terms with unclear or varying referents, such as “KM system”, in the description of deliverables.

- Do you have doubts about the way the client perceives and defines his problem? Is the client seemingly fixated in a solution, or seems to have jumped to the solution without being sure what the problem is? Do you sense a risk that the client underdefined or misdefined his problem? If this is the case, propose a two-phase project and commit only to the first DIAGNOSTIC PHASE, the purpose of which is to cleary define what is their problem.

- There are instances when the success and appropriate scope of a project depends on a decision the client has YET TO MAKE. If so, do not accept this project; propose instead another project to assist the client make that decision.

- There are instances when the outcome and appropriate scope of a project depends on factors or events that are outside the control of the client. If so, propose instead a RISK ASSESSMENT project, the output of which will be the basis of the client’s next actions.

- If project tranches are predetermined in amount and paid in a foreign currency, while project expenses are incurred in your local currency, then you shoulder FOREX RISKS. Study the fluctuations of the exchange rate over the last few years. Is it going steadily up or down? Is it steady or does it wildly fluctuate? What is the worst-case scenario during the project duration? How much contingency fund shall you set aside to cover such scenarios? Add this contingency fund in the project cost. Or, propose that the project is denominated in your local currency.

- There are projects whose scope is not easy to define or anticipate. There are clients who (from past experiences) have a tendency to stretch the scope of the deliverables or to change their authorized sign-off officer to someone who has a different or broader interpretation of deliverables. In these cases, the risk of “SCOPE CREEP” during project implementation is high. Some solutions are: propose to divide the project into smaller-scope shorter-duration phases whose deliverables are easier to define or anticipate, and define the deliverables in a clear, concrete, detailed and unambiguous manner.

- In a training project, there are clients who will pay you for delivery of the training course, but who also wants to OWN THE DESIGN of the training course and its learning materials. If you are willing to sell your IPR (intellectual property rights) on the design and learning materials, then separate the pricing of the delivery from the pricing of the design. If you are not willing to sell your IPR, then either back off from the contract or incorporate a contractual provision that you retain ownership over all IPR. You can then offer a licensing agreement whereby the client can use your IPR and pay you a per use fee (difficult to monitor use frequency) or an annual fee (a simpler arrangement).

- If the project is full or partial computerization of a business process which includes financial transactions which are vulnerable to CORRUPT PRACTICES, then suspect that there could be staff members within the organization who will resist or sabotage the project if they are in fact involved in corrupt practices. Project non-completion risk will be high. Perform your due diligence processes more thoroughly before committing yourself to this kind of project.

- There are organizations whose administrative unit (or whichever unit is responsible for the contracting process) like to take their sweet time nit-picking the details of a contract, wasting much time as contract versions go back-and-forth between you and them. Ask your client what is the typical or average length of their contracting process. If it is unusually long, beware. Ask in advance what are the REQUIREMENTS of the administrative unit. Ask for a SAMPLE CONTRACT and study its terms and conditions. It happens often that the technical people involved in scoping negotiations are ignorant or unaware of the contract requirements from their own administrative unit.

- Be sensitive to signs that there is FACTIONALISM among the managers. If one faction will engage or hire you, it can happen that the rival faction will not cooperate or support (or may even sabotage) the project.

- A technically good project proposal may be turned down because its cost is deemed too high by the client. Avoid wasting your time by asking the client beforehand what is his approximate BUDGET for the project (some will tell you but other clients won’t).

- Schedule of payments of tranches is often flexible and negotiable. The ideal PAYMENT SCHEDULE is one that will not leave your project cash flow negative at any time during the project. A client organization may have a policy of remitting the final tranche 30-90 days after the accounting unit receives the payment order or payment clearance from the unit that receives the final deliverable. If so, add the cost of money and administrative costs of advancing the amount for fulfiling your payables before the receipt of the last tranche.

- Success of project implementation can depend on COOPERATION of some key staff members of a client. If they are informed about, and better if they are engaged during the project scoping and procedure formulation, then chances of project success is better. If key staff are engaged and interested, but do not have enough time to support the project, then project success can be enhanced by a contractual provision where the client must assign specific staff to devote specific hours per week to perform SPECIFIED TASKS in support of the project.

If you wish to add your own experiences of what does not work or what are the risks during KM contract negotiation, please use the “Leave a Comment” link below.

—

=>Back to main page of Apin Talisayon’s Weblog

=>Jump to Clickable Master Index

Tags: client issues, contract negotiation, contracting process, corruption, executive sponsorship, intellectual property rights, IPR, KM, KM tool, knowledge management, project development, project risks, risks in contract negotiation, scoping, what does not work

Posted in KM tool, knowledge management | 1 Comment »

January 31, 2010

In 2002 I conducted a KM workshop for top executives of a government think-tank. All the Vice Presidents and the President were there. Most of the Division Directors were present. This think-tank does not receive annual appropriations from the national government; it survives by winning and implementing projects, running a conference facility, conducting training programs (including a masteral program) and renting out office space. They are a government organization yet they operate like a business corporation. There are years when this organization was “on the red.”

They are staffed by a wide range of dedicated experts in a wide variety of fields. They lead in innovating new government programs. They provide a good training-learning ground for upwardly-mobile development professionals: many of their program and project managers move on to high-paying positions in the government, in local and international development institutions and in the private sector.

I wanted to provide them a workshop experience that, firstly, impresses on them that KM to support core business processes is high-value KM. I wanted to show this to them in a concrete way linked to their workplace experiences.

1

After a brief lecture on what the term “knowledge” means in KM and what “knowledge management” is, I asked them the first question: “What is your core business process?”

The answer was unanimous and quick: “project management.” Many will agree with me that this government think-tank is indeed very knowledgeable and experienced in managing projects and in teaching project management.

2

My second question was: “What is your second most important business process?”

The answers were slower in coming and there were many different answers. Apparently, there is no consensus among them on what is their second most important business process. But more importantly, NO ONE mentioned a business process that in my judgment is another core business process: negotiating and winning project contracts. The alternative technical terms for this business process are “project contract negotiation” or “project development” or “project marketing” etc.

I told them: “No matter how good you are in project management, if you fail in contract negotiations you will have fewer projects to manage.”

Next I asked: “Who among you participated in successful contract negotiation during the last five years?” Almost everyone raised their hand.

3

I then formed them into small workshop groups. Their workshop task was simple and easy: From your experiences, list down what worked well (or what were the success factors) in successfully negotiating project contracts.

4

After each workshop group leader reported their group’s results to the plenary session, we discussed and consolidated all the results. The results can be summarized in one letter-size page. The participants were proud and happy recalling and documenting how they successfully clinched project contracts, and they were satisfied with the summary.

In the end I said, “This one-page summary is high-value knowledge of what works in a business process critical for your future income growth or even financial survival. Re-use this knowledge and keep improving on it.”

The process is inexpensive: it took only about an hour of time of the top executives of this organization. The potential benefit: higher likelihood of clinching next project contracts.

Using the KM framework I described before (KM Framework or F Series) and the same color coding, here is the simple logic behind this inexpensive but high-value executive workshop:

What do you think? (Please use the “Leave a Comment” link below and write your feedback.)

—

Note that there is an embedded link in this blog post. It shows up as colored text. While pressing “Ctrl” click on the link to create a new tab to reach the webpage pointed to.

=>Back to main page of Apin Talisayon’s Weblog

=>Jump to Clickable Master Index

Tags: contract negotiation, core business process, critical tacit knowledge, KM, KM tool, knowledge management, project development, project management

Posted in KM tool, knowledge management | 2 Comments »